Prof. Dr. Tom Froese (Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology)

How do mind and matter impact each other?

Cognitive science is beset by a number of fundamental anomalies that derive from the unsolved mind-body problem. Most prominent are the problem of mental causation and the hard problem of consciousness. I propose to accept these explanatory gaps at face value, and to take them as positive indications of a nondual relation: mind and matter are one, but they are not the same. They are mutually related in an efficacious, yet also non-reducible, non-observable, and even non-intelligible, manner. Hence, for the natural sciences, the embodied mind becomes equivalent to a hidden ‘black box’ that is coupled to bodily processes. In accordance with the bidirectionality of this ‘black box’, two concepts are introduced: (1) irruption denotes unobservable mind hiddenly making a difference to observable matter, and (2) absorption denotes observable matter hiddenly making a difference to unobservable mind. In this talk I will analyze these two concepts from the side of first-person phenomenology, focusing on the irruption of affectivity and on absorbed coping. A surprising outcome is that, instead of the traditional assumption of structural isomorphism, irruption and absorption from mind to matter, and vice versa, relate to each other with a structural twist. This complementary pairing of mutual impact presents a novel argument in favor of a diversification of ontology.

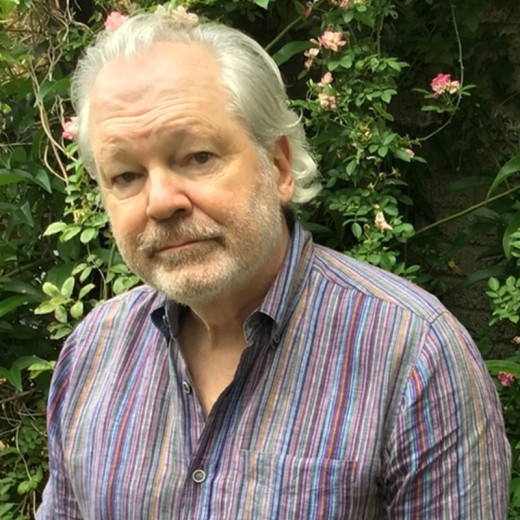

Prof. Dr. Terje Sparby

Toward a scientific taxonomy of meditative endpoints.

Extremes of human experience and development and the case of Nirvana

Meditation, in particular advanced meditation, develops toward meditative endpoints, sometimes referred to metaphorically as awakening. A well-known instance of such an endpoint is called nibbana or nirvana. The present study outlines a hermeneutically developed conceptual framework that serves to inform and guide ongoing qualitative, micro-phenomenological and neuroscientific investigations. Contemporary mindfulness teachers and different Buddhist traditions present different views of nirvana. Some define nirvana as the ultimate reality beyond awareness, while others define it as liberated or pure awareness itself. Some descriptions of nirvana focus on cessations (and particularly the cessation of suffering) and others based on affirmations (e.g., ultimate happiness). Nirvana has also been defined as ineffable, or as being characterized by paradox. These, and other, different views and descriptions of nirvana make it challenging to understand this construct, and to establish a science of advanced meditation and meditative endpoints. Here we propose an integrated taxonomy that unifies the different views and descriptions. The taxonomy differentiates between ways of entry into nirvana, nirvana itself, and the impact of nirvana. Awakening is thus understood as a many-faceted process. The proposed taxonomy provides an ontologically neutral unified view of meditative endpoints, a framework for differentiating distinct approaches toward those meditative endpoints, and a starting point for investigating awakening beyond the case of nirvana.

Dr. Radmila Lorencova (Czech University of Life Sciences Prague; College of Applied Psychology, Terezin) & Prof. Dr. Radek Trnka (Prague College of Psychosocial Studies; Czech University of Life Sciences Prague)

Experiencing Indigenous healing techniques: Inspiration for the first-person study of consciousness

The relatively recent decolonial turn has enriched contemporary scientific discourse about insights arising from Indigenous philosophies. Indigenous people formed their understanding of consciousness based on first-person experience during rituals as well as various everyday activities. On this experiential background, diverse ideas about the nature of the mind and consciousness emerged. While some Indigenous cultures understand consciousness in ways similar to contemporary scientific psychology, others developed different ideas about of how consciousness can be operationalised. Some Indigenous cultures see consciousness as a type of energy, a vital force, a kind of being or a capacity to respond to communicative signals. Traditional Indigenous healing techniques are often used by psychotherapists and clinical psychologists in a Western context. Western clients and often the psychotherapists themselves do not share the same cultural origin as the Indigenous healing techniques. The question then arises: how can Western clients experience psychotherapy inspired by Indigenous forms of healing? How can changes in perceptual and mental states induced by Indigenous healing techniques influence one’s relationship to the world? The first-person experiences of Western clients are a very interesting source of insights into what effects the application of Indigenous healing techniques may have in clients whose minds were shaped by a non-Indigenous cultural environment. These direct experiences are highly variable, showing the fine-grained nuances of conscious activity of participants. Interestingly, experiences of Indigenous healing techniques have caused long-term changes in Western clients’ ontological understanding of reality as well as in their understanding of the relationship between body and mind.

Prof. Dr. Angela Mendelovici (University of Western Ontario)

Does intentionality connect us to the external world? (And, if so, how?)

Intentionality—very roughly, the „aboutness“ or „directedness“ of mental states—is often thought to play two roles in the mind. The first is a cognitive role: our intentional states’ contents are supposed to be thought, experienced, or otherwise entertained; they are supposed to be used in reasoning, affect behaviour, and constitute our first-person perspective on the world. The second is a representational role: our intentional states are supposed to secure an epistemically meaningful connection to the world (or a connection contingent on the world meeting certain conditions), perhaps by determining conditions of truth and reference. Some precisifications of the definition of „intentionality“ take it to be whatever plays the cognitive role, while others take it to be whatever plays the representational role. This is unproblematic if we can safely assume that one and the same thing plays both roles. However, I argue that it is an open theoretical possibility that the two roles are played by distinct things and so that different definitions of „intentionality“ pick out different things. To argue for this claim, I consider various views in the literature of what plays the cognitive role and argue that what plays this role might not also play the representational role. I close by briefly offering a positive picture on which what plays both roles is a pair of distinct but related phenomena. If this picture is correct, merely entertaining a content might not automatically connect our mental states to reality in any epistemically interesting way. Instead, further facts about the mind allow for this connection. I make some suggestions as to what it would take to make such epistemically meaningful contact.

Prof. Dr. Charles Siewert (Rice University, Houston)

Consciousness and First-Person Reflection

It has been argued that the unreliability of introspective judgments shows we need to identify non-introspectively the conditions under which they are accurate, or else they will fall to a general skeptical doubt. Against this, I make a case that the evidence that introspection suffers from sources of error specific to it is much weaker than is supposed, and we would go badly wrong if we refused to rely on it until it can be externally vindicated. We are entitled to accord first-person reflection on experience a “selective provisional trust”. If we don’t, we risk undermining the conditions under which our consciousness is intelligible to us at all, and we deprive ourselves of legitimate forms of inquiry. This use of reflection can vindicate and elucidate the idea that consciousness is “subjective” in an important sense: it is essentially suited for subjective understanding and curiosity, and is always “for” some subject. This sets constraints on what can count as a satisfactory account of its nature.

Prof. Dr. Johannes Wagemann (Alanus University, Mannheim)

Clarifying the role of mental agency in participatory reality formation

While agency is undisputably relevant for shaping our cultural environments, the role of mental agency is far more unclear here and in the broader context of reality formation. Already the question of what might be ‘natural’ reality and how it is originally given to us cannot be completely answered without considering consciousness. And the relationship of consciousness to reality cannot be consistently grasped without admitting some form of mental agency, as it would otherwise amount to a purely receptive representationalism. Although the latter option seems to have become outdated in recent years, mental activity is still often equated with brain activity and conscious access to it is denied. However, empirical first-person research on cognitive processes shows that these might be constituted, at least at a participatory level, by specific micro-activities that are (potentially) conscious to and controllable by individual mental agents. This is supported, on the one hand, by study results connecting qualitative first-person data and statistically validated structures, and, on the other, by structure-phenomenological interpretation of these results in the context of psychophysical correlations. While mental micro-activities are accompanied by ‘inner agentive qualia’, stimulus-related experiences include ‘functionally negative qualia’ both of which play decisive roles in a cross-domain scenario of reality formation including not only brain processes but also dynamics of embodiment and situated embeddedness of action. Formalized by transclassical logics, this picture even allows to be extended to a cosmological-evolutional dimension suggesting that consciousness and mental agency are integral parts and participatory factors of reality.